kidney stones

- related: Nephrology, calcium renal stones

- tags: #nephrology

Overview

Approximately 7% to 11% of the U.S. population will develop nephrolithiasis, and 50% will have recurrent disease. Risk factors for developing kidney stones include male gender, increased age, White race, obesity, diabetes mellitus, the metabolic syndrome, decreased fluid intake, chronic diarrheal states, and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Clinical Manifestations

Although kidney stones may be asymptomatic and diagnosed as an incidental finding on imaging, the typical presentation is waxing and waning “colicky” flank pain that radiates to the groin. Stone movement may result in pain migration to the lateralized genitalia. The patient frequently finds it difficult to achieve a comfortable position. Nausea, vomiting, and dysuria may also be present. Microscopic hematuria is usually noted, although its absence does not exclude a stone.

Similar symptoms may be present with pyelonephritis and acute abdominal processes, which need to be considered. In addition, the ureteral passage of blood clots can mimic renal colic pain.

Diagnosis

Nephrolithiasis should be considered in all patients who present with flank pain. Costovertebral angle tenderness may be present. Microscopic examination of the urine for hematuria, leukocytes that may indicate infection, pH measurement, and crystals is mandatory but nonspecific. The presence of crystals may help to identify the type of stone. A complete blood count and complete metabolic panel should be obtained to exclude infection and acute kidney injury, and to screen for common metabolic causes of stone disease.

Definitive diagnosis is made with imaging. Noncontrast helical CT is the gold standard modality because of its high sensitivity and specificity. Although less sensitive than CT, kidney ultrasonography is less expensive, has no radiation exposure, and can be used in pregnant women or when CT is unavailable. Plain abdominal radiography has a low sensitivity and should not be ordered except to follow the stone burden in established disease.

Calcium

Eighty percent of kidney stones contain calcium; most are composed of calcium oxalate, and the remainder are composed of calcium phosphate or a combination of the two.

Calcium oxalate stones are associated with hypercalciuria, hyperoxaluria, and hypocitraturia. Up to 50% of patients with recurrent stones have elevated 24-hour urine calcium levels. This increase may be secondary to elevated serum calcium as seen in hyperparathyroidism, sarcoidosis, or excessive vitamin D intake, but is more frequently idiopathic. Hyperoxaluria can be primary or can occur secondary to increased dietary oxalate intake; malabsorption syndrome due to the binding of gastrointestinal calcium to fatty acids, allowing for increased absorption of oxalate; decreased dietary calcium; and high vitamin C intake. Rous-en-Y gastric bypass surgery is associated with hyperoxaluria and an increase risk of stone formation. The weight loss drug orlistat, by inducing fat malabsorption, is also associated with hyperoxaluria and the formation of calcium oxalate stones. Because citrate prevents calcium crystal formation, low urine levels are associated with increased stone formation. Citrate excretion is decreased in the presence of metabolic acidosis, as occurs with chronic diarrhea and distal renal tubular acidosis.

Calcium phosphate stones occur when there is persistently elevated urine pH and are therefore commonly associated with distal renal tubular acidosis and hyperparathyroidism. In addition, the use of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors such as acetazolamide or topiramate, by raising urine pH and decreasing citrate excretion, are associated with increased incidence of calcium phosphate stones. Imaging may reveal nephrocalcinosis.

Calcium oxalate

- risk: Hypercalciuria; hyperoxaluria; hypocitraturia

- urine: dumbbell shaped calcium mononhydrate, envelope shaped calcium dihydrate

- treatment: Increase fluids, Decrease sodium intake, Thiazide diuretics, Low oxalate diet, Potassium citrate or bicarbonate

- calcium renal stones

Calcium phosphate

- risk: Elevated urine pH; distal renal tubular acidosis; hyperparathyroidism. Topamax

- urine: amorphous crystals, alkaline urine

- treatment: Increase fluids, Decrease sodium intake, Thiazide diuretics, Treat hyperparathyroidism, Potassium citrate or bicarbonate

Struvite

Struvite stones occur in the presence of urea-splitting bacteria such as Proteus, Klebsiella, or, less frequently, Pseudomonas species. These bacteria split urea into ammonium, which markedly increases urine pH and results in the precipitation of magnesium ammonium phosphate (struvite). The pH of the urine will be >7.5. Struvite stones commonly produce staghorn calculi (stones that bridge two or more renal calyces) and occur most frequently in older women with chronic urinary tract infections. Because struvite stones are large and grow rapidly, they do not pass into the ureter to cause pain typical of smaller stones. Signs and symptoms typically are related to the underlying infection. Because of their association with infections, there is significant morbidity and mortality associated with these stones.

Uric Acid

Uric acid stones (<10% of stones) develop in the presence of a persistently acidic urine, which decreases the solubility of uric acid. In addition, some individuals overproduce uric acid, resulting in increased urine uric acid; both gout and increased urine uric acid are associated with uric acid stones, but hyperuricosuria is not required for uric acid stone formation. Chronic diarrhea, resulting in metabolic acidosis and low urine volume, is a common cause of uric acid stones. The metabolic syndrome is also associated with uric acid stone formation. Uric stones are radiolucent but are visualized on ultrasound and CT.

Treatment of uric acid stones includes hydration, alkalinization of the urine, and a low-purine diet. Alkalinization of the urine to pH 6.0- 6.5 with oral potassium citrate is recommended as uric acid stones are highly soluble in alkaline urine. In addition to alkalinizing the urine, citrate is a stone inhibitor and reduces crystallization. Allopurinol can be added if there are recurrent symptoms despite initial measures, especially if hyperuricosuria or hyperuricemia occurs.

A purine-restricted (not high-protein) diet is indicated in patients with uric acid stones secondary to hyperuricosuria.

Cystine

Cystine stones (1%-2% of stones) result from cystinuria, an autosomal recessive disease that presents at a young age. These stones are recognized by characteristic hexagonal crystals in the urine. They may also form staghorn calculi, and are less radio-opaque then calcium-containing stones.

Management

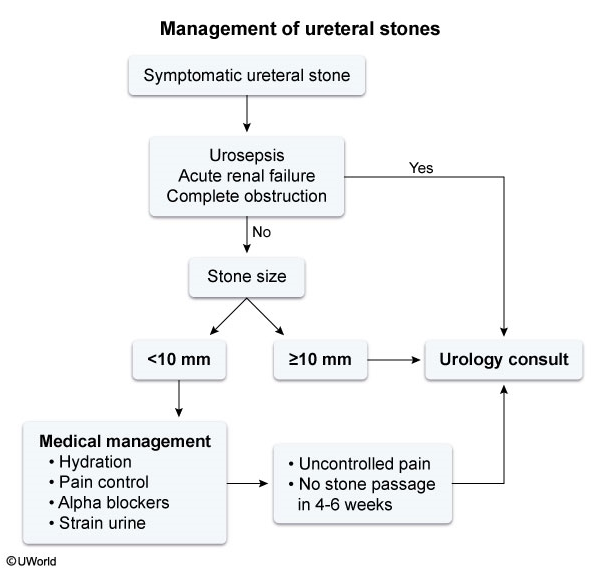

Acute management of symptomatic nephrolithiasis is aimed at pain management and facilitation of stone passage. Pain can be relieved by NSAIDs and opioids as needed. Stone passage decreases with size. Only 50% of stones >6 mm will pass, and stones >10 mm are extremely unlikely to pass spontaneously. Medications, including tamsulosin, nifedipine, silodosin, and tadalafil, appear to increase the rate of spontaneous passage for most stones and can be considered for stones <10 mm.

Urologic intervention is required in all patients with evidence of infection, acute kidney injury, intractable nausea or pain, complete ureteral obstruction, and stones that fail to pass. This may necessitate shock wave lithotripsy, ureteroscopy with laser ablation, or percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Shock wave lithotripsy or ureteroscopy is commonly employed, but stones >15 mm typically require endoscopic stone fragmentation.

Percutaneous nephrostomy tube placement relieves urinary obstruction in cases of nephrolithiasis with hydronephrosis and rapidly progressive renal failure. However, the procedure does not facilitate stone removal and is typically offered following urologic evaluation to patients who are poor candidates for emergency stone removal (eg, due to multiple medical comorbidities).

Patients should strain their urine to collect stone fragments for chemical analysis if the type of stone is unknown. In addition to the initial evaluation previously described, a 24-hour urine for measurement of volume, calcium, oxalate, citrate, uric acid, and sodium should be collected on all recurrent stone formers.

Increased fluid intake is the most important intervention to prevent recurrent disease regardless of stone composition. Urine output should be >2500 mL/d to decrease urine solute concentration.

Other interventions should be based on findings in the metabolic workup and stone analysis.

In patients with uric acid stones, management consists of increasing the solubility of uric acid by alkalinizing the urine with potassium citrate or bicarbonate; allopurinol can be beneficial if uric acid excretion is elevated.

Urinary cystine excretion can be reduced by limiting sodium intake and by alkalizing the urine to a pH >7.0. If unsuccessful, additional interventions may be required.

Struvite stones typically require urologic intervention. Before any surgical procedure, it is important that active infection be treated with antibiotics to avert sepsis. To prevent recurrent stone formation, all stone fragments must be removed from the kidney. In patients unable to undergo surgery, the urease inhibitor acetohydroxamic acid may reduce urine alkalinity and decrease stone growth; however, this is best used as an adjunct to urologic intervention.

Uric acid

- risk: Low urine pH < 5.5; diarrhea; metabolic syndrome; gout; hyperuricosuria

- treatment: Increase fluids, alkalinize urine with potassium citrate or bicarbonate, Allopurinol

- allopurinol is not main treatment

- note: urine pH from UA is not as good as from 24 hour urine because of acute infection

Struvite

- risk: Chronic urinary tract infections with urea-splitting organism

- treatment: Treat infection, urologic intervention

cystine

- risk: Cystinuria; low urine pH

- treatment: Increase fluids, Potassium citrate or bicarbonate, Acetazolamide, Penicillamine, Tiopronin